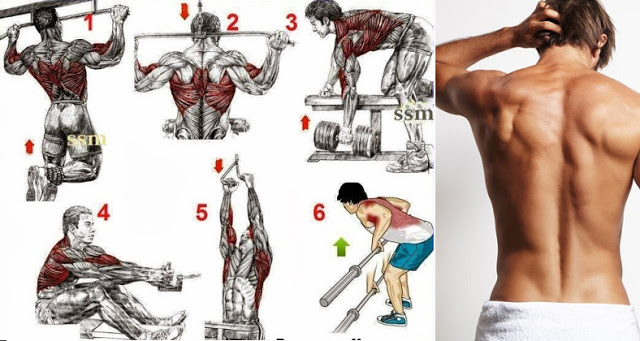

How to Really Build a Bigger Back!

Experienced lifters know that pulling exercises require more attention to detail than pushing exercises. Even once you get past the beginner stage, there’s a level of mind-muscle connection and neuromuscular awareness that needs to go into back training for it to even “take.” Logic is too often thrown out the window for the sake of another grip-and-rip set.

1 – The Dumbbell Row is a Good Lat Builder

Don’t get me wrong. Rowing movements will hit the muscles of the upper back surrounding the scapulae, but you’ll get more bang for your back by using other rowing exercises instead of the one-arm row. This is because of the body’s position relative to the dumbbell.

However, if you’re going to do dumbbell rows, you can easily optimize the movement pattern to better hit the lats. Use more of an arcing motion that “drags” the weight towards the hip and it’ll hit the lats hard. It doesn’t take a 160-pound dumbbell and a contortionist twist at the torso to make an exercise like this do its job.

2 – If You’re Pulling, You’re Training Your Back

It’s rare to see a lifter properly initiate a pull by first retracting his scapulae. Many lifters may understand this concept, but still not properly put it into practice. If this is done, most upper back-dominant movements won’t need a lot of weight to elicit a good stimulation and hit a target rep range.

Furthermore, compensatory motions, like the classic torso “jerk” pattern people use to bring the arms towards the body, usually negate any back involvement whatsoever. When we take out excessive body English, momentum, and ego from the picture, it’s worth asking if it’s even possible for 90% of lifters to get a properly isolated back pump when using heavy resistance on the lat pulldown or seated row for reps.

Even those who know how to retract the scapulae first often make the mistake of setting the shoulders “once and for all.” In other words, they keep them depressed and retracted for the entire duration of the set. That’s a recipe for technical disaster. Having good control of the shoulder blades means both making them stay put and allowing them to move. That translates to setting them and then releasing them.

The benefit of “releasing” the shoulder blades between reps is simple: You’re no longer holding an isometric and you give your body the opportunity to reset into a stronger position and allow for greater circulation to the muscles in the process.

If you’re not good at doing this, a smarter alternative would be to break things down to their derivatives. Powerlifters who are weak at their lockout practice lockouts. Take a page out of their book by practicing scapular initiations from various angles.

3 – The Lats Are the “Wings” Outside the Shoulder Blades

I’m tired of hearing people complain of sore lats after a back workout while pointing to the area beside their armpit. It’s a common anatomical misconception that the lats only create width. Not so. They actually go right down to the lumbar region and are also instrumental in developing thickness.

Guys who struggle to develop size will get a lot further by realizing this and tapping into deeper, lower-lat tissue to help increase front-to-back trunk volume. When most people think “lats,” they think pulldowns or chins. But if you’re using poor form, there’s a good chance neither of those exercises will do the job, especially when you consider the force angles needed to zero in on the lat fibers.

4 – The Dumbbell Pullover is a Good Lat Exercise

The dumbbell pullover has been an old-school bodybuilding staple for ages. For the record, I’m not bashing the exercise itself – rather the implement being used. Many use pullovers, in part, to train the lats. But the force angle used in a dumbbell pullover will only hit the top half of the lats, and only through about 40% of the movement, at most.

Once the weight passes eye level and approaches the chest and abs, gravity takes over and the shoulders, chest, and triceps begin to bear the load. And that’s without considering that it’s pretty hard to make the back contract and lock/unlock the shoulder blades while you’re lying directly on them.

To make the best of a bad situation, set up an overhead cable pulley and a dual-handled rope (or bar if that’s all you have) in front of a bench. Lie across the bench as you would in a conventional pullover, only grab the ropes instead of a dumbbell.

Since the resistance will now pull your arms overhead towards the cable pulley (and not down towards the floor), you can use your lats to contract directly against the resistance for a much greater percentage of the movement pattern. Problem solved. For best results, use a decline bench.

5 – Low Rep Training is Good for Back Size

With the exception of deadlifts, you usually don’t need to do low-rep sets when training back. The muscles of the back (especially the scapular muscles) are really there to help keep our posture erect. They maintain the long contractions that help stabilize the spine and shoulder blades and help us walk tall.

Training the muscles for endurance zeroes in on this capacity. Just like the quads respond well to high-rep training and lots of time under tension, the same holds true for the upper back. This doesn’t mean you have to chase sets of 30 reps on your seated rows; it just means you can avoid chasing sets of 3 or 5. Super-high reps would lead to grip fatigue and the arms taking over anyway.

Instead, use supersets or even compound sets – choosing one grip-intensive lift like rows or chins, and one that doesn’t involve grip nearly as much, like stiff-arm pushdowns. Extending the time under tension is a great way to do high lactate training and blast the back.

6 – You Should Always Do Pull-Ups

Pull-ups are one of the most important tools for upper body strength and development, but they don’t have to be part of every back program. And they shouldn’t be viewed as a prime choice for posture correction. As an example, kyphosis (a forward curvature of the upper spine) is a common issue. To fix this, it’s easy to gravitate to pull-ups or chins as a default major movement.

But based on the body’s starting point, the overhead position can be very harmful to the shoulders, which will present immobility in the presence of a kyphotic spine. Those with kyphosis are far better off doing more rowing motions than pull-up motions.